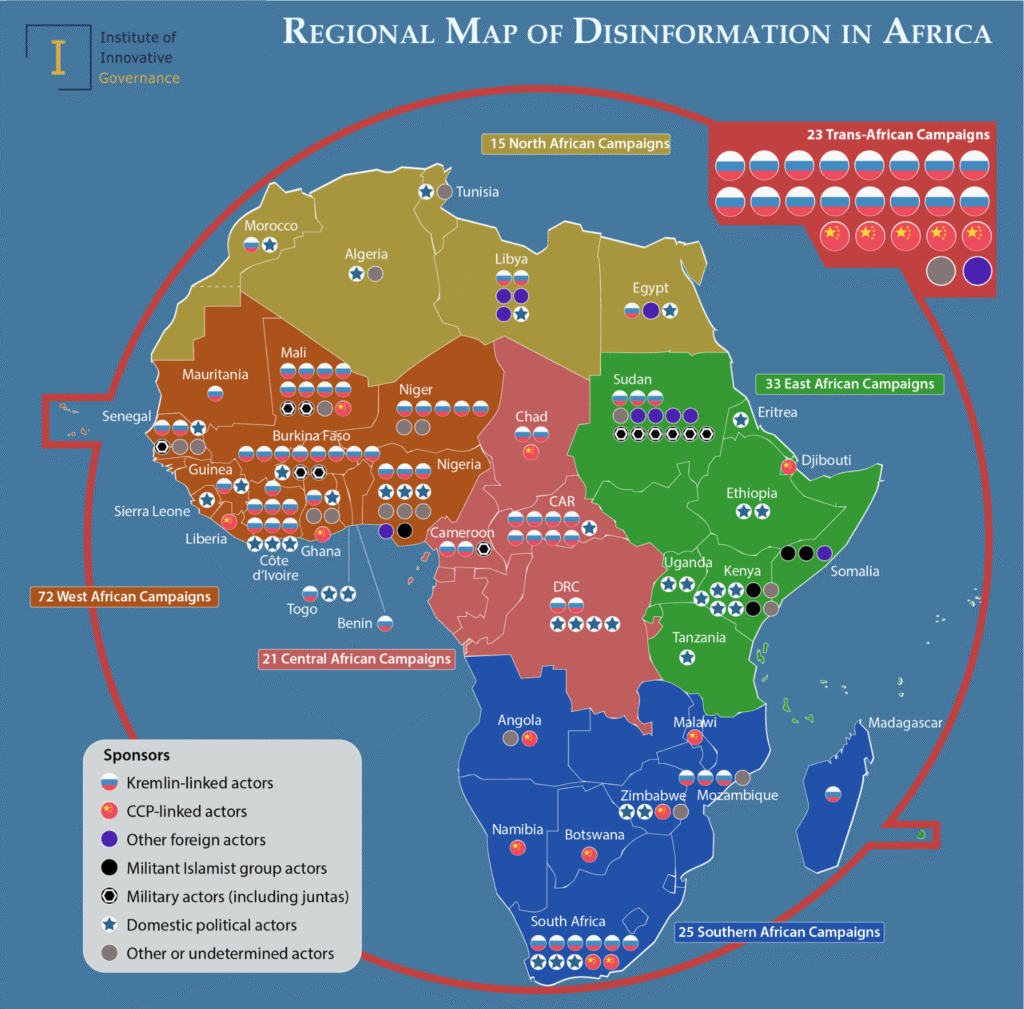

How Wagner, disinformation, and soft power are reshaping Moscow’s standing on the continent.

Russia is rapidly expanding its influence across Africa, especially in the eastern and western regions, using a combination of diplomacy, military cooperation, and media strategies. This effort is part of a broader geopolitical agenda to challenge Western dominance, particularly that of the United States and European countries, and to position itself as a powerful global actor on the continent.

A core element of this strategy involves state-controlled media outlets such as RT and Sputnik. These platforms promote pro-Russian narratives through anti-colonial messaging and strong criticism of Western policies. By framing Russia as a partner to African nations and a counterweight to former colonial powers, these outlets help shape public opinion and enhance Moscow’s soft power.

In addition to traditional media, Russia uses its embassies and cultural centres to organize events and outreach activities that subtly promote Kremlin narratives. These often focus on the war in Ukraine and present Russia as a victim of Western aggression, while appealing to themes of sovereignty and resistance.

Social media has become another powerful tool in Russia’s influence campaign. In digitally connected countries like Kenya and Nigeria, pro-Russian messages are disseminated through networks of fake accounts, bots, and manipulated content. These campaigns fuel anti-Western sentiment, deepen social divisions, and exploit local frustrations with international politics.

Increasingly, Russia is working with local influencers and digital content creators in Africa to spread its messaging more organically. In countries such as Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Nigeria, these influencers are used to amplify pro-Kremlin narratives, often without disclosing their connections to Russian-backed initiatives. They promote themes of national pride, economic independence, and criticism of Western interference, all carefully aligned with Moscow’s strategic goals.

This form of digital influence is subtle but highly effective. Russia does not need to dominate the narrative directly. Instead, it empowers local voices to echo its messaging, making its presence less visible but more deeply embedded in the public discourse.

A row of sleek white yachts bobs in calm waters, backed by glowing skyscrapers bathed in golden evening light. Posted on Facebook, the photo is presented as a majestic view of Moscow – the modern heart of Russia. There’s just one problem: the skyline belongs to Dubai.

The image, part of a post from a Facebook page identifying itself with Burundi, is operated under the name “Vladimir Putin.” The account features a profile photo of the Russian president and routinely shares pro-Kremlin content. Among the more fantastical claims is one asserting that a Russian laser weapon has destroyed 750 American fighter jets. Despite its blatant misinformation, the page has over 180,000 followers and presents itself as a legitimate news source.

Not all pro-Russian content is as clumsy or easy to debunk. Many posts are carefully constructed, deliberately shaped to sway opinion in strategic parts of Africa — without necessarily crossing the line into outright falsehood. According to mounting evidence, Moscow is investing heavily in polishing its image across the continent, especially in states deemed geopolitically significant.

In fact, Russian influence operations in Africa often succeed not because they fabricate reality, but because they subtly distort it — exaggerating facts, omitting context, or reinforcing existing grievances. As Aldu Cornelissen, co-founder of the South African digital consultancy Murmur Intelligence, puts it: “You don’t need to invent lies to tap into resentment. In many African countries, there’s a deep-seated perception of the West as a historical oppressor. Russia simply leans into that.

Instead of relying on troll farms thousands of miles away, much of Russia’s narrative-shaping now happens on the ground, crafted by local influencers who speak the language and understand the culture. Cornelissen’s firm, which monitors digital spaces for political and commercial clients, has observed how these influence operations are structured. According to him, Russia maintains a global web of core social media accounts, which are then mirrored and amplified by African accounts. Local influencers in each country pick up the messaging and tailor it to resonate with their communities.

This method is far more effective than generic foreign propaganda. Beverly Ochieng, a researcher at the US-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, confirms this trend. Speaking from Dakar, she notes that posts originating from civil rights groups in Mali and written in Bambara do not feel foreign. They seem authentic, grounded in the local experience. The average reader would never suspect a Russian connection.

These regional messengers, whom Cornelissen calls “nano-influencers,” are often paid modest sums — around ten euros each — to spread a particular narrative. When thousands of people are enlisted simultaneously, the result is a flood of coordinated content that can overwhelm social media platforms within hours. Over time, some users begin to internalize these narratives, resharing them organically as if they were their own thoughts.

The amplification doesn’t stop there. Special accounts known as “zoomers” are deployed to boost visibility through repeated shares, tags, and reposts. According to the Centre for Analytics and Behavioural Change, this tactic has been observed around the official X account of the Russian Embassy in South Africa. Other key players in the network include American activist Jackson Hinkle, a vocal Trump supporter, along with a network of South African influencers and pseudo-media outlets with clear pro-Kremlin leanings.

But Russia’s strategy extends beyond social media manipulation. It has embedded itself in Africa’s media infrastructure. In the Central African Republic, often seen as a testing ground for Moscow’s influence, Russian operatives founded a radio station called Lengo Songo in 2018. According to leaked testimonies, Russian handlers often dictated the editorial line, supplying talking points and shaping local news coverage to suit their goals.

RT, Russia’s state-run news network, has also been aggressively expanding its reach on the continent. Though banned in many Western countries, RT remains available via satellite in much of Africa. In 2022, the network announced the launch of a new English-language media hub in South Africa, which it claimed had already begun operations. RT also broadcasts in French for audiences in francophone Africa and regularly features local journalists from Mali and beyond, some of whom are linked to the country’s ruling junta.

The Kremlin has also been accused of secretly operating content channels like African Stream and funding news outlets such as African Initiative. The latter positions itself as a media bridge between Russia and Africa and is widely believed to have ties to the Wagner Group, the Russian paramilitary outfit founded by the late Yevgeny Prigozhin. African Initiative maintains a strong presence on Telegram and social media, with accounts that range from openly branded to deliberately opaque. In Mali, the outlet even works with a local journalism school and has recruited top students as field correspondents.

The propaganda isn’t confined to the digital world. In May 2024, African Initiative organized a photo exhibition in Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou. The displays ranged from tributes to the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany to curated narratives about the war in Ukraine’s Donbas region. According to one local source, residents are especially receptive to stories about military victories against terrorists. Videos showcasing Russian weaponry and trained soldiers are easily interpreted as signs of a strong, reliable ally.

These themes are reinforced in pop culture as well. The 2021 Russian action film “The Tourist” portrays a heroic Russian soldier stationed in the Central African Republic. In the video game African Dawn, developed by African Initiative, players can choose between Sahelian troops and their Russian advisors or the Western-backed forces of ECOWAS. The message is not subtle. Through such “militainment,” the Kremlin pushes its central narrative: the era of Western colonial dominance is over, and Russia is the continent’s true partner in progress.

Russia finds many opportunities to drive this point home. One of the most notorious examples came in January, when French President Emmanuel Macron lamented that African leaders had failed to show sufficient gratitude for France’s military assistance. His remarks triggered outrage across the continent. African Initiative seized on the moment, quoting a St. Petersburg political analyst who called for “new global partners” like Russia, who would treat African nations with greater respect.

This sentiment taps into deeper historical currents. According to CSIS’s Beverly Ochieng, Russia continues to benefit from the lingering memory of Soviet support for anti-colonial movements during the Cold War. The USSR backed the African National Congress in South Africa, the MPLA in Angola, and revolutionary governments in countries like Ethiopia and the former Zaire. These alliances may have been more strategic than idealistic, but they’ve left a legacy that Moscow is now keen to revive.

The Soviet Union’s involvement in Africa was never just about solidarity. Its interventions were driven by geopolitical calculus and a desire to compete with the West for influence during the Cold War. One of the earliest examples was the Congo Crisis in 1960, when the USSR supported Patrice Lumumba, a charismatic leftist leader who sought to unify the newly independent Congo. Moscow placed its bets on Lumumba, but within months he was assassinated. The country spiraled into a brutal five-year civil war, and the idealistic promise of Soviet-backed independence collapsed under the weight of internal chaos and external meddling.

Later, in the Ogaden War between Ethiopia and Somalia in the late 1970s, the Soviet Union switched sides mid-conflict, ultimately backing Ethiopia. With Soviet tanks and arms, Ethiopia pushed back Somali forces. The episode marked a turning point. It became clear that the USSR’s relationships in Africa were no longer framed by ideology, but by pragmatic interests. As the Cold War progressed, Soviet engagement became less about revolutionary ideals and more about securing influence, resources, and allies.

By the time Mikhail Gorbachev launched his reforms in the mid-1980s, many African governments had grown wary of Moscow’s shifting loyalties. The appetite for socialism was waning, and newly independent states either distanced themselves from the USSR or rebranded old party leaders as democratic presidents. Some, like Angola and Mozambique, retained pro-Soviet governments for decades. Others, including Ethiopia and the Congo, moved away from communism entirely.

Despite this mixed legacy, Russia’s involvement in Africa is still viewed favorably in some circles. In South Africa, for example, the ruling African National Congress remembers the USSR as one of the few nations that actively supported its fight against apartheid. Western countries, by contrast, were slow to distance themselves from the white minority regime. This historical memory gives Russia a narrative advantage today, especially when it portrays itself as a long-time ally against imperialism and oppression.

Yet this romanticized version of the past is far from the whole truth. While the Soviet Union promoted anti-colonial rhetoric, it also waged imperial wars of its own—in the Caucasus, in Central Asia, and in Eastern Europe. Enslavement and exploitation were not foreign to its history. Still, for many in Africa, the distinction is less about historical accuracy and more about the current power dynamics. Russia claims it has no colonial past in Africa, and that alone sets it apart from Europe in the minds of some audiences.

This anti-colonial framing, though rooted in Soviet-era slogans, has been refined for the digital age. Today, Russia casts itself as the champion of the Global South, fighting an unfair world order imposed by Western powers. In this narrative, the war in Ukraine isn’t about expansion or imperial ambition. It’s framed as a defensive battle against NATO aggression—a message that resonates in countries still grappling with the legacy of Western intervention.

Which African countries have thrown their support behind Moscow? In most cases, it’s the ones where democracy is either weak or non-existent. Zimbabwe, Eritrea, and Uganda all maintain close ties with the Kremlin. These regimes, often led by long-serving strongmen or military juntas, align easily with Russia’s authoritarian model. Elsewhere, such as in Sudan, Libya, Mali, and the Central African Republic, Wagner Group has taken on a central role in shaping the security environment. These are not traditional alliances, but rather fragile dependencies built on resource extraction, repression, and transactional politics.

Wherever there is instability, wherever peace is fragile and the state is weak, Russia finds a foothold.

Ukraine, for its part, has had to start nearly from scratch. While Russia inherited a robust network of embassies and Soviet-era ties, Ukraine only recently began establishing a diplomatic presence on the continent. As of now, Ukraine operates around a dozen embassies in Africa, with plans to open more in countries like Rwanda, Mozambique, and Botswana. This is a promising step, but it also means that some ambassadors are responsible for as many as five or six countries, often spread across vast regions. For instance, Ukraine’s diplomatic affairs with the Central African Republic are currently handled from the embassy in Morocco.

This limited presence creates challenges. Real engagement requires more than official visits. It needs people on the ground—Ukrainians who understand the local context and can communicate in both official and native languages. In many African countries, the language of government might be French, English, or Portuguese, but the real conversations happen in Swahili, Bambara, Lingala, or Zulu. Diplomacy in Africa is not just about politics; it’s about cultural fluency and trust.

Russia, meanwhile, has even enlisted its Orthodox Church to expand its influence. Since the establishment of the Moscow Patriarchate’s exarchate in Africa, Russian Orthodox parishes have opened in over 30 countries, with half of them appearing just in 2022. The timing is not accidental. According to Ukraine’s Center for Countering Disinformation, this religious outreach is another layer of soft power, aimed at boosting support for Russia on the world stage under the guise of defending Orthodox Christians.

The church, like the media, reinforces a specific image. It tells African audiences that Russia is not tied to colonialism, racism, or slavery. This, of course, overlooks the historical realities of serfdom and imperial conquests in Russia’s own backyard. But that doesn’t stop the message from spreading. In the information war, perception often matters more than fact.

Russia’s growing presence in Africa isn’t just about media narratives or diplomatic charm offensives. At the heart of its strategy lies the Wagner Group, a shadowy paramilitary network that blends military operations with psychological warfare, digital manipulation, and resource exploitation. Its operations stretch from Libya and Mali to Sudan, Madagascar, and the Central African Republic—and the group’s tactics are as brutal as they are calculated.

The case of the Central African Republic offers a clear blueprint. Wagner entered the country in 2017 at the invitation of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, whose government was floundering after years of civil war. Western-backed peacekeeping efforts had made little headway, and Touadéra, desperate for results, turned to Moscow. Wagner forces helped crush rebel factions, secured key cities, and protected the president’s grip on power. In exchange, they were granted access to gold mines and diamond fields.

Similar patterns have emerged elsewhere. In Mali, Wagner’s services cost the government an estimated $10 million per month. In Sudan, the price tag was even higher—around $250 million in mineral rights, much of it tied to untraceable gold shipments. These deals rarely appear in official documents, but the evidence has mounted over time. What Russia offers is security for sale, backed by a quiet but relentless campaign to control the narrative and reshape public perception.

Once Wagner gains a foothold, it launches synchronized information campaigns designed to discredit opposition groups, elevate the host regime, and legitimize its own presence. In the Central African Republic, Russian flags appear at pro-government rallies, and Facebook pages flood with praise for Moscow’s support. The goal is not just to win battles, but to make the population believe that Russia is their protector and the West their oppressor.

At the same time, Wagner maintains just enough instability to stay relevant. It crushes rebellion but avoids complete victory. A lasting peace would make its services redundant. Instead, it fosters a state of dependency—militarily, economically, and psychologically. Governments continue to pay, and Wagner continues to benefit from mining revenues and political influence.

This blend of force and narrative, of soldiers and storytellers, has become a hallmark of modern Russian power projection. And the parallels with Ukraine are hard to ignore. Many of the same disinformation tactics tested in Africa have been deployed in Ukraine—particularly in the early stages of the war. The use of proxy forces, fake news campaigns, social media manipulation, and deniable military actors form a consistent playbook.

But while Ukraine has the institutional strength and international alliances to push back, many African nations do not. That vulnerability makes them ideal targets—not just for short-term influence but for long-term strategic gains. Through Wagner, through state-backed media, and through the Orthodox Church, Russia is weaving a web of loyalty and leverage that spans the continent.

What’s more, the narratives being pushed are not confined to the countries where Wagner operates. Stories seeded in French-speaking Central Africa find their way to neighboring states. Narratives crafted in Mali are echoed in Niger, Chad, and even the Democratic Republic of Congo. The influence spreads like a ripple, far beyond the original point of contact.

Russia frames itself as the voice of the Global South, the champion of sovereignty and resistance against Western domination. And in doing so, it revives and repackages old Soviet-era myths—this time for a digital audience, hungry for new heroes in a world where trust in Western institutions continues to erode.

For Ukraine, the challenge is twofold. It must strengthen its own diplomatic and cultural presence in Africa, while also exposing the darker truths behind Russia’s engagement. This means more embassies, more partnerships, and more direct communication in local languages. It also means highlighting how Wagner’s promises of protection often come at the cost of democracy, sovereignty, and freedom.

Russia’s Africa strategy is not just about geopolitics. It is about shaping a worldview. One in which Moscow stands not as an aggressor, but as a liberator. One in which Ukraine is cast as a puppet of the West. One in which colonialism is condemned — unless it wears a Russian face.

And unless this narrative is confronted head-on, its reach will only grow.

"The project 'Strengthening the Capacity of Ukrainian and African Civil Society Organizations to Detect and Counter Russian Influence in West and East Africa' is supported by the International Renaissance Foundation."